|

The explosion at Baddesley Pit on the 2nd May 1882 was the worst disaster in the history of the pit. It was also the 5th worst in the Midlands area, which included the coalfields of Warwickshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire.

A new area was being worked known as the Deep Workings and to get there the men had to go down a steep incline. Water had become a problem.

Various methods of removing the water had been tried but proved unsuccessful. It was therefore decided to provide power underground to run steam pumps to remove the water. The consultant mining engineer, Mr Gillett, who was based in Derby, agreed to the installation of a boiler providing that it was placed on a brick platform and a brick archway was built around it. He also said that it should only used one day a week. Mr Parker, the manager, had the boiler installed but the brick archway was never built and it was used continuously. We shall never know why as Parker was one of those who lost his life and was therefore unable to account for his actions at the subsequent enquiry.

The boiler had only been alight for a short time when the miners noticed the coal above the boiler was starting to glow red. They threw buckets of water over it and later Parker rigged up a hosepipe to constantly spray the area with water. This was the worst thing he could have done as throwing water onto coal does not put it out it merely makes it smoulder.

At about 10 o'clock on the evening of May 1st, Joseph Day, a deputy, was going to relieve his father, Charles Day, who had been on duty since 2 o'clock that afternoon. As he went down into the mine he encountered thick black smoke in the shaft. He immediately found his father and reported this to him. Their first thought was for the 8 men and a boy who had gone down to the deep workings at about 8 o'clock. They had gone to work the nightshift reluctantly as on the next day the pit wasn't going to be working. The pit wasn't working full-time owing to bad trade at the time. But Parker wanted some repair work done. Charles and Joseph Day tried to get to the men but were beaten back by the thick smoke. The only clean air was about a foot above the ground. Charles sent Joseph to raise the alarm. Parker soon organised a rescue party. The owner, Mr Dugdale and his agent Mr Pogmore were also informed. Mr Pogmore sent a telegram to Mr Evans, Chief Inspector of Mines for the Midlands area and to other mining engineers. He and his son, Frank, went personally to fetch Reuben Smallman. When he arrived at about 3 o'clock in the morning he took charge of the operations.

The men worked all through the night trying to build wooden screens covered in a special brattice cloth which the smoke couldn't penetrate in order to push the smoke back down the incline and create clean air in the intake airway. At about 8.30am the next morning a terrific explosion occurred. It wasn't a gas explosion as Baddesley pit was free from gas. It was an explosion of coal dust, which caused flames to rush through where the men were working. Most of the rescuers were badly burned. Everything went pitch black as all the lamps were dropped and went out. The ones who were not too badly hurt helped the others to get out and more men went down to rescue the rescuers.

Mr Arthur Stokes, Assistant Chief Mining Engineer arrived at the pit shortly after the explosion occurred. He met Reuben Smallman who was so badly injured that although Mr Stokes knew him quite well he could hardly recognise him except by his voice. Mr Smallman told him what had happened and that it was believed that there were three men still down the pit including the owner, Mr Dugdale. In spite of Smallman's warning that the condition of the mine was dangerous, it was now full of smoke and noxious gases and there could be another explosion at any time, Stokes agreed to go down and rescue these men. Other mining engineers, Mr Spruce and Mr Mottram from Tamworth had also arrived together with Mr Marsh who was the manager of nearby Hall End colliery. They agreed to go with him. But none of these men were familiar with Baddesley Pit so Charles Day and another miner called William Morris agreed to go with them. They succeeded in bringing up Mr Dugdale who was injured but still alive. He was taken to his home at nearby Merevale Hall. These same men went down a second time and brought up young John Collins. Rowland Till, the carpenter, who had been building the wooden screens, was still down there. Charles Day was by now completely exhausted and had been given the news that three of his sons were all very badly injured. New volunteers were therefore called for. Charles and Joseph Chetwynd together with William Pickering went down with the others. Charles Chetwynd went ahead on his own into the smoke and the darkness and found Rowland Till. He took a rope with him and tied this round the injured man and with the help of the others they managed to get him to the pit bottom and then up to safety. Rowland was brought out alive but died soon afterwards.

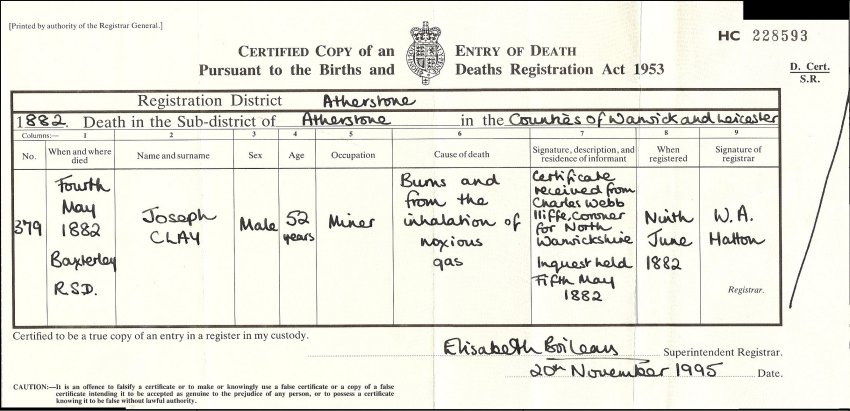

In all 23 of the rescuers subsequently died from their injuries, including the owner, Mr Dugdale, his agent Mr Pogmore, the manager Mr Parker and the underviewer Mr Clay.

The next morning a decision was taken to seal off the mine, this being the best method of putting out the fire. It was not possible that the 9 night shift workers could still be alive. This brought the total death toll to 32. Of those 32, 23 were married men, many of them with young children.

A Relief Fund was quickly set up and donations were received from all over the country. The widows received 5 shillings a week for themselves and 2 shillings and sixpence for each child under the age of 13. Help was also given to the injured men and to the able-bodied men who had difficulty in finding new work after the pit was sealed off.

Albert medals were later awarded to 10 brave men who attempted to save the lives of others on that terrible day. First class medals went to Reuben Smallman, Arthur Stokes, Charles Day and Charles Chetwynd. Second class medals went to Samuel Spruce, Thomas Mottram, Frederick Marsh, Joseph Chetwynd, William Pickering and William Morris. The medals were presented by Lord Leigh, Lord Lieutenant of Warwickshire at a special ceremony at the Corn Exchange, Atherstone on the 12 February 1883.

The Relief Fund Committee decided that all the rescuers deserved some kind of recognition for their efforts and special commemorative Bibles were presented to all the rescuers. In the case of those who had died they were presented to a member of the family.

It was 6 months before any attempt was made to re-open the mine. Some of the bodies were not recovered until August 1884 over 2 years after the disaster. The body of young Joseph Scattergood was never recovered. The area of the deep workings was bricked off and never worked again.

Work, however, did recommence in other areas of the mine. The pit remained in the ownership of the Dugdale family until nationalisation in 1948. It finally closed in 1989. The area remains as wasteland, despite various plans being put forward.

Two memorials have been erected dedicated to the men who worked in the Baddesley pits. They take the form of half a winding wheel. One is situated on Baddesley common on the site of the old Maypole pit, opposite the Maypole Inn. The other is situated in Baxterley, by the side of the village pond, next to the Rose Inn. So, although mining in the area has long since finished the memory of the pits, the men who worked in them and the explosion remains.

|