|

Go direct to Explosion! - the story

COMMENTARY

Daniel Parton

The genesis of my dissertation Explosion! came during the late Spring of 2000. I had already decided that I wanted to pursue the creative writing option, as I felt it was my strongest suit, over literature and language, and also it would be the one I would most enjoy to research and write.

The idea for writing a story based on the 1882 Baddesley Colliery disaster came whilst I was visiting an exhibition in my hometown of Atherstone in Warwickshire, on the history of mining in the area. As the disaster is the most famous event to happen in local mining, a large area of the exhibition was devoted to it, showing actual documents from the aftermath, reproduced newspaper coverage from the time, and a written account of what happened. I read these with great interest, for two reasons; firstly, I have been raised on the story, and I knew that several of my ancestors were involved, and one, Charles Day, my great-great-grandfather, was awarded the Albert medal for his efforts in trying to rescue the trapped men, so I was interested to read what he did. Secondly, I was struck by what an amazing story it was - the acts of bravery, the tragedy of the explosion and subsequent deaths, and how it became apparent that it could have been avoided.

As I read, the idea dawned on me that a story about what it was like - the rescue effort and actual underground explosion would be very interesting, especially if it was written from the miners' perspective. I also knew that I could easily get hold of the relevant documents and information that I would need in order to research the story, as my Mother has a binder full of pieces about the explosion, mostly written at the time of, or just after when it happened, by people who were involved. She was also involved in the exhibition, so I could gain access to the items on display after the exhibition had finished.

I started to research the story in the late summer of 2000, finding out the names, ages and occupations of those who were killed in the explosion, and also those who were involved and injured in the rescue effort. This enabled me to use the names of real people in my story, which would give it a sense of reality, which is what I wanted to create. It also told me of the scale of the disaster - thirty-two people died in all.

After this I started to build up a chronology of the events leading up, during, and after the explosion. At this point, I didn't know how much data I would need to be able to write eight thousand words. Compiling the chronology was time consuming, as I referring to three or more sources - newspaper reports from the time, a written account (date unknown) which included a narrative from Charles Day himself, M.P Arnold Morley's reports on the disaster from 1882 and 1884, and various other pieces, such as reproduced diary entries from Henry Sanders, or pieces written at the time of the centenary in 1982. Matters were complicated by the fact that some reports contradicted each other. For example, some reports state that there were three explosions in the mine; others said there was only one. This meant a definitive answer was impossible, so I decided to write that only one occurred, as that came from the clearest account, as the timings for the three explosions wasn't given in the other, which I wanted as I was trying to get the timings fairly accurate for authenticity.

As I progressed through my research my understanding of the events increased, and the basic skeleton of my story started to emerge - how it all started because of a boiler, how the manager, Mr Parker was negligent (and therefore prime candidate to be the villain of my story) and that the men were trying to rescue the trapped men when they were caught in an explosion of dust.

By October 2000, I had enough information to be able to start a first draft. I had several ideas for the opening, including starting with the explosion, then going back to the lead up, explaining how it came about, but I settled on beginning just before the first anniversary, setting the scene with the lead character of Charles Day, before going back to April 1882, and telling the story in chronological order. However, linking my opening scene to the chronological beginning proved difficult, so much so that it only appears in the second draft onwards.

However, after this initial problem, writing the story proved to be quite easy, because of the research I did before starting to write, and the chronology I'd come up with, which meant I did not have to keep going through the original material every time my story progressed. However, one problem I have encountered is finding a title for the story, as I didn't see an obvious one, or one that wasn't corny or trite. It was only after the third draft that I came up with it.

I did encounter areas where I found gaps in my research, so I put a note in the margin to remind myself for when I did more research. After reading different documents, and analysing more closely items I'd used before, I was able to go back to my draft and fill in the gaps, making my story more coherent.

By using documents and reports from the time, I was able to glean a fairly accurate picture of the events that unfolded at the Baddesley Colliery and by using these facts I could blur the border between fact and fiction. I know I could never get a fully accurate story, because, as mentioned previously, some of the reports and accounts contradict each other, and others have been lost or destroyed, and obviously no survivors can be interviewed. However, I can get data, such as the length of the rescue effort (from ten o'clock on April 30 to eight thirty the next morning, when the explosion occurred, then up to eleven or twelve midday to rescue those caught in the blast) right, which will help engender a sense of realism.

I have fictionalised some parts however - the start in particular, most of the dialogue, and some events. One event which I changed for dramatic purposes was where the Colliery owner, Mr Dugdale, went into the shaft to help with the rescue effort. In reality, he did go down, but only to see what was being done to save the men. When the explosion occurred, he'd only been in the mine for half and hour, whereas in my story, he'd been down for about three hours. I did this to help portray him as a hero from the gentry, helping his fellow men. It is documented that he was a well liked and respected man, and I felt that having him help would convey this in a way reality wouldn't have, especially within the confines of the 8000 word limit, which means there is relatively little time for character development.

The explosion scene is also fictionalised, but from things such as Charles Day's account, the record of the injuries the men suffered, and knowledge of other mine explosions, I gained an idea of what it might have been like. I also tried to imagine what it could have been like from a miner's perspective - the pain, the terror and the panic. Hopefully this is reflected in the passages describing it. The passage itself was shortened after the second draft, as the character of Henry Sanders is edited out, as he didn't appear at any other stage of the story.

I used a lot of dialogue in the story, as I feel it adds to the realism, which is why some small talk appears, as it does in real life, and it is also convenient for plot development, such as when Reuben Smallman explains his plan to rescue the trapped miners.

I also tried to get the dialogue as close to how the characters would have spoken, again for realism. Getting the accent was not a problem, as I live only three miles from Baddesley, and I have friends and relatives who live there, so I know how the people there talk. For example, 'h's are dropped, such as "'e" instead of "he", and there are some colloquial words, such as "yoursen". I was helped by finding a piece written by Reg Day in the local dialect, which gave me other dialect words and spellings that I was not previously aware of. The mining terminology, such as "deep workings", was mentioned in the documents I used in my research.

I also tried to distinguish the dialogue between friends and between worker and superior (e.g. Charles Day and Mr Parker) where in the second case; the worker would speak differently than he would when conversing with friends. Also, the dialogue from the educated characters is differentiated from the workers, as the educated ones would use a more formal register.

Several things impressed me when completing the drafts. The most major was the ease in which I reached the 8000 word limit, and breached it, requiring me to edit certain passages. I feel that I could easily have written thousands more words on this story, as there are so many details that have either not been mentioned, or have only been skimmed, for example the setting up of the relief fund for the victims, where the vicar of Baxterley, Hugh Bacon, was instrumental, and would have made an interesting story itself. A longer story would also have enabled me to flesh characters out, so the reader would hopefully become more involved in the story and more concerned as to what happened to them. I could also include more characters, such as Henry Sanders, who appeared in the first two drafts of the story, but thereafter was edited out, because he only appeared in one passage, and I needed to bring the number of words down.

I am happy with the form of the story, with its traditional beginning-middle-end structure, and a fully formed plot, with closure at the end. I feel that to have a different structure would have been detrimental to the story, and it may have got lost somewhat, under the weight of an unusual form, whereas a traditional form suits the story.

To put the story into a specific genre would be difficult, as it takes from several genres, such as the disaster story and the Victorian novel, to name two. I also think that the story successfully blurs the boundaries between fact and fiction, as I think to spot the fictional elements in the story is difficult, unless you are acquainted with the facts of the explosion. The dialogue is apart from this though, as it is too detailed to have been taken from reports, where only snippets appeared, although it is still true to the time and the area. This blurring is an effect I wished to create, as it means that the realism is not compromised. This is also why I don't make it explicit that it is a fictionalised account, or use a post modern device such as having a narrator who breaks from 1882 to comment on the events from a contemporary perspective.

I am satisfied with the way that the story has turned out, I feel it has drama and tension, and could grab and hold the reader's attention for the duration, which was one of my initial intentions. I feel I have done the story justice, although a higher word limit would enable me to go into greater depth, as I feel it is a story that should be told and not be forgotten, even though it happened over a century ago.

EX PLOSION! PLOSION!

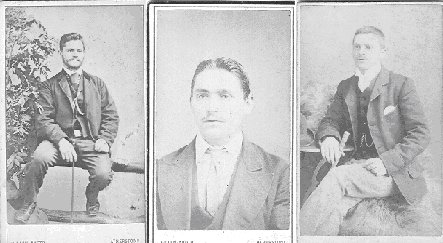

Pictures of the Day brothers, Joseph, William and Thomas

It was the sound of it that he remembered most. The deafening bang followed by the whizzing sound as the wall of flame ripped through the shaft, burning everything in its path.

He opened his eyes, to find himself still in the graveyard. He looked back to the headstones, and the names on them; Joseph Day, aged 31; William Day, aged 22; Thomas Day, aged 20.

"My boys," he murmured, as a tear escaped from his eye. "It should never have happened. Never," he added bitterly, shaking his head. He looked around, surrounded by graves.

"I know too many here. Too many who should still be alive," the rain, which had been falling lightly for some time then got appreciably heavier, so he turned away, looking for shelter, still oppressed by his memories.

As he walked back through the streets of Grendon, he saw a young woman carrying a baby. He said "Hello" to her, and she reciprocated, smiling weakly, but they didnt stop to talk, as neither wished to be out in the rain for longer than they had to be.

"Sarah Ann Evans, she's another who's suffered," he thought, "her babbie'll never know 'er father either."

He turned down a dirt track lined by small terraced houses. He continued on to his own, which was a typical miners cottage, small, not especially modern, but well kept by his houseproud wife, who knew she didn't have much, but made the best of what she did have. He opened the door, wiped his boots on the mat, and took his hat and coat off.

"Im home dear."

"Hello Charles," she replied.

"Weathers turned bad out."

"Arr, it has, come by the hearth or you'll ketch y'death."

Charles silently acquiesced, even though he didn't feel cold. He watched as she fussed about the room, tidying. It seemed to Charles that she was always tidying now, even if it seemed there was nothing to tidy. He didn't remember her being like this in years gone, but maybe in years gone, he had had other distractions. As he watched her, he noticed just how much she had aged in the last year since the disaster. Her hair was noticeably greyer, her face had become gaunt, the colour had gone from it too, and the lines were more pronounced. Now, she was an old lady.

An uneasy silence developed as the small talk of before evaporated. They both had the same thing on their minds, that the next day was the first anniversary of the disaster, the day that life for everyone in the villages of Baddesley, Baxterley and Grendon changed forever.

"It should never 'ave 'appened 'Liza. The boys should still be here, not in the churchyard."

"We both know that…but we have to keep going."

Charles mumbled a reply, as the feelings of bitterness welled up inside him again. He shut his eyes, and again he was back in the mine, choking on toxic smoke, unable to see, with screams ringing out all around. Quickly he opened his eyes, and swallowed hard. The impending anniversary had made the memories that had started to fade seem alarmingly fresh again. Not that he'd ever be able to forget, as nobody could forget the things he'd seen.

It had all started when a new boiler was installed inside the mine a little over a year before, which allowed the new steam pump, bought to pump water from the deep workings [The deepest shaft in the mine], to run at full power. However, within a day, because of the flame that issued from the boilers funnel, a fire had been started in the coal in the roof above it. It was quickly extinguished, and Charles, as Senior Pit Deputy, reported this to the manager of the mine, Mr Parker. As a result, he ordered that a dome should be excavated above the boiler. This didn't solve the problem however, as there was still a patch of coal above the boiler which was burning, and glowing red.

This didn't go unnoticed by the men who walked past it on their way to the deep workings everyday, and they reported it to Charles, who in turn reported back to Parker.

"Thu coals still burnin' down in the pit over the boiler, sir."

"Thank you, Day. I'll put it down in your report."

"Thank you sir." Parker wrote out Charles' report, as he always did, as Charles was illiterate. As he put his mark at the bottom of it, Charles thought everything hed asked to be included would be in there. However, this wasn't the case, as Parker had omitted Charles'concerns over the burning coal. He knew that to make the boiler safe would require George Congreave, the pit builder, to put a brick arch around it, which would cost money, money the pit couldn't afford. Parker also reckoned that nothing would happen, as there had never been a major accident at the mine in the thirty-two years since it had opened in 1850. As a result, nothing happened and the patch kept glowing, much to the puzzlement of the miners.

"I fowt you told Mr Parker 'bout the coal, Dad?" asked Joseph, Charles'son and deputy.

"I did, but 'e aint dun anyfin, so Im gonna tell 'im again, and try an mek 'im do summat."

"Good, cos it cant go on wif men throwin water on it every so often."

So, once again Charles told Parker, who told him curtly,

"You're worried about nothing, Day."

"But I fink throwin buckets of water on it aint enough."

"Are you tellin me how to run this pit?"

“No, sir, but it's dangerous."

"Alright, I'll do something about it."

"Thank you sir."

Parker did look at it, and decided that a hose should be attached to the engine, so water could be sprayed on the coal, which had the effect of blackening the area for a while, but underneath it was still burning.

The next Wednesday, April 26, Mr Gillett, the mines consulting engineer, and Parkers immediate superior, paid one of his occasional visits to check how the mine was working. He saw the boiler, and commented on the fact that a brick arch should be built immediately. However, Parker knew that Gillett wouldn't be making another visit for a few months, so he was safe to carry on as he had been, without anyone making him install the arching.

The boiler was put out a few days later anyway, as an accident with the feed pipe to the boiler meant that the pump wouldn't work, and couldn't be fixed until the next day, May 1. So the man on duty of overseeing the boiler, John Webster, raked out the boilers fire, and having nothing else to do went home. The coal however, was still glowing red.

The area around the boiler was closed off, and nobody else saw it until four oclock the next day, when out of curiosity a boy, William Shilton, went to have a look at the boiler, to see what everyone had been talking about. He looked in, and was disappointed to see the boiler inactive. He didn't pay much attention to the patch of glowing coal above it, which had now begun to smoke. He thought it was strange, but reckoned that the deputies and manager would know about it, and he didn't want to say anything in case he was punished for going where he shouldn't have, so he went up the shaft and back home.

Later that day, Charles Day was completing his underground examination, in his capacity as Senior Deputy, and was on his way back to the cage when he met the night shift coming down.

“Hello, Joe. What are y'doin tonight?"

"Mr Parker said we were to dint [Lower] thu rails, t'do some repairs later," replied Joe Orton.

"How far does Mr Parker want 'em to go?"

"Fair way, bout four hunnerd inbye [towards the coal face]."

"Very well. Is that all you huv t'do?"

"Arr. I didn't like comin to work tonight though. The pits goin to play tmorrow [The pit was shut the next day], so there's no necessity for us to 'ave to work at all."

"That's right," added William Knight, "I was waitin' and I fowt they'd send me word not to come."

"I know, but Mr Parker wanted this done now," replied Charles, shrugging. The men nodded resignedly.

"Were lucky though, I reckon," said George Bates, "cos the coal aint sellin an Mr Dugdale could uv shut the pit, but 'e aint." The others nodded again, acknowledging that another owner may have laid them off.

"Have you got any wagons t'put the dirt in?" asked Charles, looking around him. There was a shaking of heads. "Right, I'll help fetch a hoss [Horse], so y'cun move the wagons from inbye."

With that he left six of the night shift to go down the incline, whilst he and William Blower went to fetch a horse from the underground stable. On the way, Charles and William, good friends, were chatting.

"Are you still interesting in them gilliver trees [Type of flower roots], Charlie?"

"Arr, Bill, I am."

"Well as soon as they're ready to draw, I'll bring you some round."

"Thanks, Bill, thats really good of you."

When they reached the stable, they untethered a couple of horses, and Bill took the reigns, to lead them to the deep workings.

"Right, I'll see you t'morrow, Bill."

"Night Charlie."

As Bill went down, Charles carried on back to the surface, passing on his way the other two members of the night shift, John Ross and William Smith, who were sending timber for the rails down to the bottom, before joining the others.

At ten oclock, Charles'son, Joseph, came to shift him, saying worriedly,

"Father, there's smoke in the shaft."

"What?" exclaimed Charles.

"Smoke look fr yoursen [Yourself]. Get on the cage and I'll ring the bell."

Charles got on, looked up and saw a veil of smoke, which as he ascended, got thicker, and to stop himself choking, he had to cram his scarf into his mouth. The smoke also had the effect of making it seem that the cage had broken, as he couldn't see or hear it moving. He was just starting to panic when, to his surprise, the cage reached the surface, and he lurched out, coughing and hacking.

"Wass goin on?" asked the banksman [Cage operator], who'd seen Charles come up.

"Theres a fire in the shaft!" replied Charles between hacks.

"My God! How bad?"

"Not sure, I want to go back down an find out. Can you bring the next cage up for me?"

The banksman quickly brought up the cage, which Charles got on to and descended to the bottom of the other shaft. Once down, Charles went looking for Joseph, who he quickly found, seeing his light in the distance. As he got closer, Charles could see the worry etched on his sons face.

"Joe, whats the matter?"

"The smokes here comin right up the hill."

Charles closed his eyes, as the severity of the situation started to fully dawn on him. Fires in the mine were uncommon, and this was much bigger than anything hed seen before, and much more dangerous.

"Have you seen the night shift come out, Joe?"

"No, they must still be down the bottom."

"God, no! … Right, you go and tell Mr Parker, and anyone you can find who can help, I'll stay here and try to get to the night shift and warn them."

"But Father, are y'sure you want to stay down 'ere? I could stay if you wanted?"

"No. I'm the senior deputy, its my responsibility."

Joseph acquiesced and headed off to raise the alarm. Charles went to the incline, where the smoke had already got thicker, and now went down to about a foot off the floor. Putting his scarf back in his mouth, he tried to make his way through, but the smoke was too thick and he was beaten back. He tried to call them, but the smoke mercilessly attacked his throat, meaning that his shouts came out as croaks, croaks that were returned by silence.

Charles knew the fire was between him and the men, and that the boiler was also. He silently cursed as he thought of that patch of coal above it. However, the thought of his friends and fellow miners being trapped was uppermost in his mind, and this thought spurred him on to make another attempt to reach them.

As Charles was doing this, Joseph was raising the alarm. He contacted Parker, and also started to raise some of the men who lived closest to the mine, who, even though it was past eleven oclock at night, all made their way over as quickly as they could. In turn, Parker had contacted the owner, Mr Dugdale, and his agent, Mr Pogmore (who had rushed to nearby Nuneaton to fetch the mining engineer, Reuben Smallman) and Mr Gillett, the consulting engineer, who were now all on their way to the mine.

After more fruitless attempts to get through the smoke, Charles went back to the surface to get some air, where he was soon joined by other miners, who he told about the situation. When a significant number had arrived, Charles asked the group,

"Is there a carpenter here?"

The men looked around, and one man, Rowland Till, stepped forward.

"Do you think y'can build a fireproof screen, Rowland?"

"Course. I'll go an' get me tools."

Soon after, Charles, Rowland and several others were in the shaft, assembling a large screen, which was covered in fireproof cloth. When it was finished, Charles gave his directions to the others,

"We need t'pick it up and then slowly walk towards where the fire is.” Along with five others, Charles then picked up the screen, and started to advance into the smoke. The screen allowed the air to flow and pushed the smoke over the screen, allowing the men to advance, leaving the shaft behind less smoky. Their progress was slow, but spurred on by each others encouragement, they kept moving.

After over an hour in the shaft the men had got around one hundred yards further down the shaft, but the ever thickening smoke became too much for the men holding the screen, and they were forced back.

As they came back to the surface, the frustration was plain to see on their blackened faces. They all knew that as time went on, the chances of getting those trapped out alive grew less and less. They also knew that they couldnt give up until there was no chance of finding any survivors. They came from a small community, where everyone knew everybody, so they were searching for friends and relatives, not just miners.

It was about three o'clock when Reuben Smallman arrived, along with other local officials. A visibly worried Parker had also arrived and was trying to organise the growing number of miners that had gathered at the pithead. Charles greeted Reuben, and along with Parker, explained the situation, and how they had tried, and failed to get through the smoke.

"We got s'far, then it was just too much f'rus, the men couldn't hold the screens," said Charles

"But you did get over a hundred yards in?"

"Arr, 'bout that."

"Right, I see." Reuben stopped and thought, "I think it would be best to erect a fixed screen, along with using movable ones, as that would mean if we did get beaten back, we wouldn't lose all the ground we'd made."

Parker and Charles nodded.

"Is there any chance of getting some equipment out?" asked Parker.

"Thats not my concern." replied Reuben, curtly, then continuing "Is it possible to shut the entrances to thother shafts, as that'll force all the air down the deep workings."

Parker, somewhat chaste, nodded and went to get someone to shut the entrances, whilst Charles and Reuben organised the party to go down.

At four oclock, the party, composed mainly of young fit colliers, and others trying to reach trapped relatives, went down, six at a time into the smoke filled shaft. There, under Reubens guidance, another attempt at getting through the smoke using fireproof screens was made. Even though they went as fast as they could, progress was still frustratingly slow, as the smoke which was getting thicker all the time choked the men with every breath they took, and stung their eyes until each had tears streaming down his face, but they kept going. After they had progressed about a hundred yards, a screen was fixed in the shaft, which meant that the smoke could now only come so far, and that they could progress from there.

As this happened underground, above ground a horse and carriage drew up, and three well dressed men got out. A buzz of interest went around the crowd, which had gathered around the pithead, even though it was the middle of the night.

"Its Mr Dugdale," said one.

"Oos that wif im?" asked another

"Thats Mr Pogmore, e's Mr Dugdales agent, the others 'is lad."

The men walked briskly towards the pithead, through the crowd which parted to let them through. Parker met them at the pithead.

"Sir, you've come."

"Yes, Mr Parker. I couldnt stay away from a disaster at my own colliery, I want to know if the men have been saved."

"Not yet, sir, but there are men in the shaft trying to reach them as we speak."

"I want to join them."

"What?" exclaimed Parker.

"There are my employees trapped down there, and I want to see that everything is being done to save them, and if I can help, I will."

"Its extremely dangerous though sir the shaft is full of smoke."

"I dont care, man, just get me down there. You should already be there Mr Parker, dont you care about them?"

"Of course," he retorted. "I was about to join them."

So Parker climbed into the cage with the other three, and went down into the smoke. The descent was slow, and the amounts of smoke and heat grew as they got lower. "This," thought Parker, "is what going to hell must be like."

When they reached the bottom, they saw the smoke was being pushed further and further back down the shaft. Eli Smith and William Day were lifting timber nearby, to take forward to Smallman, and the carpenters, Rowland Till and George Ball.

"Mr Dugdale, sir," said Eli, hoarsely, the smoke having affected his lungs.

"What can I do to help?" asked Mr Dugdale.

"Erm…" Eli's mind blanked, as he was overawed by having the owner speak to him.

"You'd best go an' see me Father an' Mr Smallman, sir. They'll tell yu' wot t'do." interjected William, pointing down the shaft. Mr Dugdale followed Williams direction and went. All around, men were working hard, driven by adrenaline, whilst more men were coming down, including another of Charles' sons, Thomas. Reuben Smallman was working at the head, directing the effort. Amid the hammering, shouts and other noise, he suddenly heard a tinkling sound."QUIET!" he shouted, as loudly as his smoke filled lungs would allow. The message gradually filtered back, and an eerie silence developed. The came the tinkling sound again, the sound of a bell, rigged on a wire running the length of the shaft."Its comin' frum darn the shaft!" exclaimed Rowland Till."Then they must be still alive," said Reuben, smiling, "Theyre still alive."

"They can't be that far away neither," added Charles.

This new hope meant that the efforts were redoubled, and gave new energy to tired limbs, which had been in the shaft for several hours. Dawn had broken above ground, which meant more people came to the pithead, and more men had gone down to try and help, meaning the shaft was getting crowded, with over thirty men underground. Charles went to the onsetter [Underground cage operator], Charles Albrighton.

"Theres too many in 'ere, its getting dangerous, stop sendin 'em down."

"Right-ho. Y'look knackered Charles. Ere, ave a drop of me brandy, that'll see ya right."

"Ta, Charlie," said Charles, taking the flask and swigging. "D'ya mind if I tek this wif me?"

"Nah, I reckon you need it more than me."

"Ta. I'd best be gettin' back."

Back at the head of the party, Rowland Till was hammering fireproof material onto another screen. However, it would prove to be one of the last things he'd do, as it was then that a massive explosion of coal dust ripped through the shaft, an ear-splitting bang followed by a wall of fire, turning the atmosphere into a toxic mix of smoke and carbonic acid. The screens were smashed like matchsticks, and the men in the shaft took the full force of it. Nobody was left uninjured, either being burnt by the fire, choked by the unbreathable air, hit by the flying remains of the screens, or all three.

The blast also broke almost all the lamps, pitching the men into total darkness, which combined with the screams from the badly injured added to the hellish scenario. Screams that turned to croaks as they inhaled the smoke, adding to their pain.

Some started to panic, running around blindly, trying to find their way back to the cage, and ultimately, safety. But they only succeeded in running around in circles, getting no closer, only tripping over those who were too badly injured to get up unaided.

There was panic above ground too, as the crowd had heard the explosion. Men rushed to the shafts opening to try and get down and help those caught in the blast, whilst the women, a good number being mothers, sisters or wives of the men, could only worry and try to comfort each other, as they were powerless to do anything else. Eliza Day knew her husband and three of her sons were down there, and was nigh on hysterical, despite efforts to clam her down.

After a few minutes, when nobody had come back up, those above ground started to fear the worst. However, it was then that they heard the sounds of the cage slowly ascending, slower than normal, due to the damage it had sustained in the blast. When it reached the surface, the first men were helped out into the morning sunlight. As they were helped out, there were screams from the crowd, as they caught their first glimpse of the men. Most were horrifically burned, especially on their hands, arms and faces the parts most exposed when the fireball had hit them head on. The fireball was of such an extreme temperature, that the burns were very deep, so deep as to render some virtually unrecognisable, their faces being little more than bloody pulp.

As soon as they reached the surface, doctors, who had rushed from Atherstone and other neighbouring towns and villages as soon as theyd heard what was happening, treated them. None of the doctors had seen anything as bad as this before and most blanched at the horrific sights in front of them. They did all they could to ease the mens suffering, but they knew it wasnt enough, and that some wouldnt survive much longer.

Eliza Day had pushed her way through the crowd to the shaft entrance, her eyes full of tears, looking for her husband and sons. She soon found Charles.

"Oh my Lord," she breathed.

"Hello, Eliza."

"You're alive," she said, relieved. Charles nodded slowly. "But…how come youre not as burnt as the rest?"

"I wuz lucky. I wuz near the cage, away from the blast, so I never got the worst on it."

Eliza hugged him, and Charles winced with pain.

"Have you seen the boys?" asked Eliza.

"Arr. Two on em are really bad, I fink they were wif Charlie Albrightons lad near the front."

"Oh please Lord no…"

"Go to them, they need you." Charles pointed to where a doctor was treating Joseph and Thomas, and Eliza rushed over to them.

Charles was sitting near the pit entrance, receiving attention from a doctor, when he was approached by three well dressed men, who introduced themselves as; Mr Stokes, an Inspector of Mines, whod arrived by train from Derby, Mr Spruce, a mining engineer and his assistant, Mr Mottram, whod come from Tamworth.

"Do you know where the manager is?" asked Stokes.

"Mr Parker? He's over there," Charles pointed to where most of the injured were, "but badly injured, I fear."

"Ohh, I see. Have all the men managed to get out?"

"Im not sure, I fink there are still men comin' up, as there was a good number down there."

Charles was then overcome by a fit of coughing. When he stopped, he noticed a well-dressed lady, who he recognised as Mrs Dugdale, had joined the men.

"Excuse me, but have any of you seen my husband? I've looked, but I cant find him."

Charles shook his head. “I'm sorry Mrs Dugdale, I dont think he's come back up yet."

Mrs Dugdale gasped, and a tear escaped from her eye. The cage was still bringing men back to the surface, but the gaps between it going down and coming back up were growing ever longer. By half past nine, nobody was coming up, and it was realised that to save Mr Dugdale, and others, a rescue party would have to be sent down.

One was quickly formed, involving, Stokes, Spruce and Mottram, as well as Mr Marsh, the manager of nearby Hall End Colliery, whod arrived to help, and a young collier, William Morris.

"I want to go down too," said Charles.

"I dont think thats a good idea, you've been down all night and you're not well." replied Stokes.

"Im fine."

"Let im go down," said Charlie Albrighton, who was tending to his son nearby 'e knows the pit as well as anyone."

"The man has a point, you can come," conceded Stokes.

As the party went to the cage, the crowd, which now numbered hundreds cheered loudly, giving more hope that other survivors could be found. After they had been gone for some minutes however, with no word coming back to the surface, the anxiety grew, as everyone knew there could be another explosion.

The crowd's fears were allayed when the cage came back up a few minutes later, although they were disappointed when only Mr Spruce emerged. He did bring good news though - Mr Dugdale had been found badly injured, but alive. This elicited another cheer, as the news went around the crowd.

Spruce descended again with blankets to wrap Mr Dugdale in. As he reached the bottom, he could hear a faint voice calling regularly, which was Mr Dugdale directing Marsh and Stokes to where he was lying, as they couldn't see him because of the smoke. After some time they came back into sight at the top of the incline, crawling on their hands and knees, dragging Mr Dugdale as fast as they could, as they knew that if he remained in the pit much longer, he'd succumb to the effects of the smoke and damp.

The others rushed over to help Mr Dugdale, and to get him into the cage, but as they did this, Charles was distracted by more sounds coming from within the smoke, a faint moaning, followed soon after by a different moaning.

"There are others still alive!" exclaimed Charles.

"We'll come back for them," replied Stokes.

When the cage reached the surface, the crowd strained to get a look at Mr Dugdale, but the Police, who'd also arrived on hearing about the fire, held them back, as he was taken to the engine house for treatment. Few noticed that on his return Charles had collapsed, his injuries and exertions of the last twelve hours having finally caught up with him.

The smoke had taken its toll on all the rescuers though, but after about half an hour's rest, they felt ready to return. Charles tried to join them again, but he was restrained by those around him, who knew he was too weak, and that another trip underground would probably kill him. Begrudgingly Charles relented, and the party, amid more cheering, went down without him.

In the pit the men made several journeys into the smoke, each time going further than before, and they were rewarded by finding two more men alive, though very badly burnt and virtually asphyxiated by the toxic smoke. They too were slowly and painfully brought back to the surface.

Now Stokes thought that everyone was out of the pit, and when he asked the men around the pit entrance, they agreed with him.

"Right," said Stokes, "then we can get on with-"

"Wait!" shouted Charles, "I'm sure someone's still down there."

"Who? These men say that everyone has been brought out now."

"I'm sure I 'eard Rowland Till darn there - an 'e ain't come back."

"I'll check the list," replied Stokes, taking the list of saved men from Spruce. He scanned it, and found that Charles was right, Rowland Till was still missing.

"You're right Charles, but I don't think its worth going down again, he must surely be dead by now. Besides, it would just risk more lives."

"But 'e might still be alive," protested Charles.

"He's right," piped a voice from the crowd, "if 'e's alive, we should do everyfin to try an' save 'im. If you don't wanna go, I will."

"What's your name?" asked Stokes, taken aback at the young man's forcefulness.

"Charles Chetwynd [Pronounced 'Chetin'], sir. I work at Hall End pit, under Mr Marsh."

"An' you're willin' to go down and try to save Till?"

"Yes sir."

"You're aware of how dangerous it is?"

"Yes sir. But I wanna try."

"Very well, but I still think it's an unnecessary risk."

So Charles Chetwynd and two other volunteers descended into the pit, armed only with some lengths of rope which they'd found lying on an earth bank, and determination. At the bottom, he tied one rope around his waist and gave the other end to his companion, so that if the smoke became too much and overcame him, he could be dragged out. He then stuffed his handkerchief into his mouth, and started to crawl backwards down the incline, so he wasn't looking directly into the smoke. His progress was slow, and he had to go further down the incline than previous rescuers, as Till had been at the front of the party when the explosion occurred.

After what seemed like an eternity to Charles, he finally touched on Till's prostrate body. He tied a length of rope around Till's body, which made him moan in pain, and then started to drag him up the incline.

It was only when they reached the surface that the full extent of his injuries could be seen. He had wounds from being hit by airborne pieces of the screen he had been working on, but he was also shockingly burnt over most of his body, almost down to the bone in some places. He couldn't talk because his tongue had shrivelled up, and his eyelids had been burnt away, leaving his eyes a blinded mess. It was all he could do to breathe.

Charles Chetwynd was hailed as a hero back at the surface, with people congratulating him on his bravery, and shaking his hand. Mr Stokes made a special effort to shake his hand, admitting he was wrong. Charles just shrugged; saying he just knew it was the right thing to do.

Whilst this was happening, four men walked past carrying Rowland Till on a stretcher, on their way to his house, which was around two hundred yards from the mine. They had got about half way when Rowland Till's heart stopped, putting him out of his torture. He was the first.

The next day dawned, and again people started to congregate at the pit. They had gradually dispersed after Rowland Till had been rescued, as there was little else to see. There were no more explorations, as all the rescuing party had been got out, and because of the smoke and fire, it was impossible to get to the nine trapped miners, who it was reckoned, would be dead anyway. The relatives of those trapped refused to believe it though, they clung to the hope that the smoke hadn't blown their way and that if the fire could be put out, they could be saved. The colliers who knew the mine knew better, and were resigned to the loss of their friends.

Charles Day knew this too. He thought back to his conversation with Bill Blower, on the last time that he ever saw him, about the "gilliver" trees. "He always could grow them good", he thought "best in the village." Charles couldn't believe he was gone, but then he couldn't believe the events of the past two days either. However, he couldn't escape the reality that three of his sons were critically ill from their burns. He tried to shut it out, and from a sense of duty, went down to the mine.

The site was busy when he arrived. People were still coming to look, even though the only thing to see was smoke rising from the shaft. There were several officials at the pit mouth, assessing what to do. They included Stokes, Spruce and Marsh, who had been joined by Mr Gillett and Mr Evans, the Midlands Chief Inspector of Mines. They greeted Charles, and resumed their discussion

"I went down and I was nearly suffocated," said Stokes, "theres no chance of putting the fire out," the men murmured agreement.

"I think," said Mr Evans "after consulting with you, and also Mr Parker and Joseph Clay, who are both gravely ill, the best course of action is to seal off the mine, to starve the fire of air."

"I think thats the only option," agreed Spruce, as the others nodded. "Those men can't be alive."

They then decided on the way to close the blowing and drawing shafts - by lowering scaffolding, covering it with canvas and old bags, then above the scaffolding planks, eighteen inches of mortar would be placed. Stokes and Evans would oversee the operation, and Charles was assigned to assist the men.

As they went their separate ways, Charles was approached by a tearful woman he recognised as William Knight's wife, Elizabeth.

"D'yu know what they're doin' Charlie?" she asked, "Are they shuttin' up the pit?"

"Yes, they're goin' to shut it up to try an' put the fire out."

"But they can't! Will's still down there - wot if 'e's tryin' to get out an' 'e can't?"

Charles sighed heavily. "I'm sorry, but he's gone, Lizzie. There's no chance he's alive. I'm sorry."

She broke down again at this, sobbing uncontrollably in his arms, as the realisation that her husband was dead started to hit her. Charles did what he could to comfort her, but he knew nothing he could do or say would make her feel better.

Watching this scene from the road was William Shilton. He'd seen everything that had happened, and knew all about the fire. He couldn't stop thinking about what he'd seen a few days before, and his feelings of guilt were starting to overwhelm him. He'd realised that the manager hadn't known about it, and that now nine men were entombed, and others had died trying to save them, and to him, it was all his fault. However, he also knew that he couldn't say anything about what he knew, because emotions were running so high, he thought he'd be killed. He turned, blinked away his tears, and walked away.

The sealing of the shafts took most of the afternoon. Everyone involved felt strange, knowing that they were sealing in nine men. Conversation was non-existent as they tried to finish the job as quickly as possible. The men were almost finished when Charles noticed one of his daughters, Ann Maria, running onto the site. He stood up and walked towards her. As she got closer, he could see that she was crying. Instantly he knew what had happened. She ran into his arms, sobbing,

"They're gone, Father, they're gone."

"They?" asked Charles, barely above a whisper, as the word stuck in his throat.

"Will and Tom."

For Charles, this was too much to bear. After all he'd seen and done over the past three days, his resolve had remained, but this news broke it. He sank to his knees, holding his daughter, and started to cry uncontrollably.

Charles was by no means the only one though. His was a scene repeated in many houses in the villages, as one by one, the men caught in the explosion started to die, watched by their powerless families. When Charlie Albrighton's son, also called Charles, succumbed on Wednesday night, he became the eighth rescuer to die from his injuries.

More followed the next day, the day the inquest into the disaster started in the nearby town of Atherstone. Young Eli Smith lay in his father's house, and seemed to be rallying, enough to be able to answer when his father asked him if he knew what had caused the explosion.

"I - its all through P-Parker's fine pumping engine." This sentence was enough for old Eli. He'd known about the pump, and like his son, and a lot of others, had thought it wasn't safe. Now he was faced with the terrible knowledge that all the deaths could have been avoided, a knowledge which only compounded his grief. A grief which old Eli faced a few hours later, when Eli's condition suddenly worsened, and he died, aged just nineteen.

In the Day house, hardly a word was spoken. Eliza quietly mourned her two dead sons, and also tended to Joseph, her eldest, who was also badly injured, but he was strong and she had hopes for him. Charles sat in the corner of the room where Joseph was. He'd hardly said a word since he'd returned home on Wednesday. Outwardly he looked ill - he was still suffering from the effects of the explosion, and hadn't eaten properly since then either. Inside he was worse. Still shocked from the things he'd seen, but also grieving for his sons and the friends he'd also lost, and now he was also wracked with guilt at having not been present when William and Thomas had died. He felt he'd let them down in their final hour, and that that he should have been there for them. That was why he was with Joseph, he wasn't going to let his eldest son die without him. He didn't share his wife's hope of him surviving.

Charles vigil lasted until the evening. He'd sat through Joseph trying to speak, but failing because he was so badly burnt, and watched, along with the rest of his family, Joseph slip away, watching his chest slowly rise and fall, until it fell, and didn't rise again.

Friday was a dark and wet day, befitting the mood which hung over Baddesley and neighbouring villages Baxterley and Grendon. Whenever another rescuer died, the news would be around the villages within a few hours, adding to the collective sense of grief. Life had to go on however, and with this in mind, small knots of people walked the three miles down to Atherstone's Town Hall, to either watch, or give evidence at the inquest.

Charles was the first witness called. Dressed in his Sunday best, he solemnly took the stand. It had taken all his strength, physical and mental, to get there, and he steeled himself to answer the coroner's questions.

"William Day was my son," he began, "he wuz twenty-two years of age and unmarried."

"When did you last see him alive?" asked the Coroner, Dr Illife.

"Just before the explosion on Tuesday, sir, then at 'ome, 'e wuz fearfully burnt. He died on Wednesday."

"Did you have any conversation with the deceased after he was brought home?"

"A little sir."

"Did he mention the explosion at all, or how it happened?"

"No, I don't think he mentioned it at all, sir. He just asked us to pray with him."

As Charles answered the same questions about Joseph and Thomas, he was aware that in the gallery, his wife Eliza, and two of his daughters, Ellen and Ann Maria were crying. He turned in the stand so he couldn't see them, focusing totally on Dr Illife, knowing that it was likely he would break down too.

After Charles stepped down, a sombre stream of people got up to confirm the death of their relatives, and to answer "no" to the question of whether they mentioned anything about the explosion. All except Eli Smith, who made sure his son's words - "Its all through Parker's fine pumping engine" were heard by the entire room. There was an audible gasp from the packed gallery, followed by a raft of whispering, as some knew, but others were surprised - but it seemed to apportion blame. Some whispers were angry, as the miners knew the boiler was unsafe, but were ignored.

After the final identification, Dr Hales, who had examined the bodies, took the witness stand, and gave his conclusion that all the men had died from burns and inhaling inflammable gas. Nobody was surprised.

Dr Illife concluded that the deaths were of an accidental nature, and gave the order for the burial of the dead men, then adjourned the inquiry until further deaths were reported.

As the gallery dispersed from the Town Hall into Long Street, the main road through Atherstone, everyone was talking about what Eli Smith had said, and what it meant. Charles let his family go on ahead, stopping to talk with Charles Albrighton, John Webster and George Congreave.

"You tol' Parker about the boiler didncha Charlie?" asked Charles Albrighton.

"Arr, several times. I even asked 'im to put it in me report a few times."

"'Ow cum 'e didn't do anyfin?"

"Dunno. Maybe cos it'd cost."

"Well," added Congreave, "when I put the foundations on th' boiler I said it needed a brick archway over it, but 'e said Mr Gillett 'ad towd 'im not to build one, and that there was nuffin 'e could do."

"Thats strange, cos we could all see it weren't safe," said Charles.

"Arr, 'specially as that bit of coal wuz on fire above it," agreed Charles Albrighton.

"Weren't you the last wun in charge a it, John?" asked Congreave.

"Arr, I wuz."

"What wuz the coal like?"

John's eyes flicked away from the others and he swallowed hard, then coughed, before answering,

"Well…it were glowin' red, so I went an' told Parker abaht it, then I went wum [Home]. Next thing I know, pits on fire."

"Then why didn't Parker do anyfin about it?" asked Congreave exasperatedly. He was met by silence.

"He never said anyfin about it t'me," said Charles, almost in passing. He thought it was strange that Parker hadn't said anything, but he was too tired to think deeply, and quickly forgot about it.

"When d'you think the pit'll be open again, Charlie?" asked Congreave.

"Not for a good while. It'll be ages before that fires out, and then it'll be a while more before its ready to open."

"Looks like we're all out of jobs, then."

"What'll we do for money?" asked Charlie Albrighton.

"Dunno, but I don't think Mr Dugdale'll let us starve," replied Congreave. The others nodded, thinking that when the local squire recovered, he'd help his employees out in some way, as that was the kind of man he was.

Mr Dugdale was unable to help though, as unbeknownst to them, he was declining. Initially his doctors had high hopes that he'd recover, but after making some progress, his condition suddenly worsened, and never improved. He died slowly that Friday evening. His death was much mourned in the villages, as he was a popular and respected man. Everyone knew that the coal from the pit hadn't been selling, and that he kept the pit open, running at a loss, to keep the men in employment. Going down the pit to help only further enhanced his reputation. He was certainly more mourned than Parker was, when he too succumbed a few days later.

However, also in Atherstone that day was an extraordinary general meeting of the Guardians of the Atherstone Union, who proposed to set up a relief fund to help the men and their families, who now had no income. The motion was carried unanimously.

The next week was no less emotional, as the people of the villages committed over ten men to their premature graves, whilst still more rescuers died from their injuries. The burials were an ending, but also a beginning, as those left behind started to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives and community. They knew it was going to be hard, but they had to go on. Charles had five other children to consider, and most of those newly widowed had families to care for too.

The relief fund was started that week too, and as the explosion had made headlines nationally, received donations from all over the country, especially from other mining areas, where people empathised with the miners plight. By late May, the fund had received enough money to start paying the twenty-one widows and remaining injured men. It wasn't a great deal, only five shillings per week, plus two shillings and sixpence for every child under thirteen years of age, but it saved them from destitution.

The other two hundred and fifty plus workers at the mine were given temporary relief, and help in finding new jobs. Some went to Hall End Colliery, whilst others dug part of the common land for the vicar of Baddesley. In the summer months, some went out into the fields to labour for local farmers. Slowly, life went on in the villages.

In February 1883, the disaster was brought back to the front of everyone's thoughts, as on the afternoon of the nineteenth, at the Atherstone Corn Exchange, a large gathering of people witnessed the presentation of ten Albert medals - the highest award for bravery in the country.

For Charles, one of the recipients, it was an immensely proud moment when Lord Leigh, the Lord-Lieutenant of Warwickshire, shook his hand and pinned the medal onto his left breast, in recognition of his bravery in doing everything to try and save his friends. Charles Chetwynd, like Charles, also received a first class medal, for rescuing Rowland Till, as did Stokes and a recovering, but badly disfigured Reuben Smallman. Six second class medals were also awarded, to William Pickering, Joseph Chetwynd, William Morris, and Messrs. Spruce, Mottram and Marsh.

The spectre of death hung over the proceedings though, as everybody knew that in total, thirty-two men had died in the disaster. Thirty-two men who should still have been alive. They also knew that later that week the pit was going to be opened for the first time since it had been sealed nine months earlier. It brought back painful memories, but also gave hope that the pit would soon be reopened, and the men could have their jobs back.

Those hopes were dashed when it was found that the fire was still burning, and also that the water level had risen, as no water had been pumped out since the disaster. A further investigation in April found three bodies, and after Reuben Smallman and Morgan, the new mine manager, had examined the state of the men's candle boxes and food, they deduced that the men had died before the fire was discovered.

It was a final bitter irony, piling fresh agony onto those who had just started to get over the disaster. Many, including Charles, struggled to overcome this news. As he sat in his front room, he couldn't help but feel bitter. The fact that as a result of the disaster, mine safety regulations would be tightened nationally and prospective managers would need more qualifications wasn't a consolation to him. It wouldn't bring his sons back. He felt they should have been tighter before, as the disaster should never have happened. Something he could never forgive.

---ooOoo---

Copyright © Daniel Parton 2001

Back to top

|